Dungeons & Degenerate Gamblers review: a fickle but fun roguelike that stretches Blackjack to the moon and back

Slack-handed?

Hm. Hmmmm. Right. So, what have we got here? There’s my Blood Donor card, which reduces the value of the hearts I play, but also heals me. That’s fine, actually. Reduced score means I can squeeze in another card for more healing. If I can pull my Tarot card, I'll deal damage with each heal, and I’ve already pulled two scratch cards for yet more quick damage. Now, if I can just pull a Jack, I can plonk down the King Of Space And Time for a brutal finisher. That’ll transfer everything on my side over to my opponent’s, forcing a bust for a nice final chunk of hurt and…

Oh, you thought we were playing Blackjack? At one point, so did I. That was a much simpler time. Before the NFT ape. Before the glitch cards. Before the flippin’ Charizard. Whatever other issues I might have with it, I can’t lavish enough praise on the shuffly-slappy strategy of Dungeons And Degenerate Gamblers for taking Blackjack - a game that’s only even mildly interesting if you happened to have wagered your favourite leg on it - and rendering it captivating without altering the fundamentals beyond the point of recognisability. It alters almost everything else beyond that point, mind. But even when you’re scorching a necromancer’s library card with your Gerald From Riviera, the mundane pull of risking it all on a single card, for a slightly better outcome, stays strong. I think I might appreciate Blackjack more now, honestly. D&DG makes you realise how sturdy those fundamentals really are, maintaining form even after being creatively trolled and pounded from all sides, like the canvas in Lawler vs Kaufman.

It’s probably more fair to say it’s D&DG’s twist on those fundamentals that does the heavy lifting though. As with traditional Blackjack, the goal is to get as close to 21 as possible without going over. You snaffle a card, then you can either stand on your current score, or have another. You face off against a roster of opponents. One might be a bouncer. The other might be a talking rat. Whoever gets closest to 21 wins the round. D&DG’s first twist is that losses don’t hurt your chips - they hurt your health. If you stick on 17, and the rat scores 19, you lose two health. But if the rat busts - again, by drawing over the limit of 21 - you’ll deal damage equal to your entire score.

But you might actually want to keep going at this point, even after watching your opponent bust, and so the health system cleverly incentivises risk even past the point of a traditional Blackjack victory. The stupid rat has busted when you’re sitting on 16, but they’ve got 17 health left, so maybe you want to risk another draw to finish them off before the next round starts, and perhaps doesn’t go quite so smoothly. With this, D&DG stresses the importance of not just winning, but winning well.

You’ve only got 100 health total, and your opponents often have around 30 to 50, so busts can be devastating for either side. To help you out, each opponent displays the number they’ll stand on, letting you plan around this. If either side does hit the magic 21, then their score gains bonus effects based on the suits that make it up. If you hit 21 with 10 clubs and 11 hearts, you’ll deal double damage from the clubs, and also heal 11 health from the hearts. Spades generate shield, which is lost before health when you’re damaged, and diamonds generate chips.

All this goes for your opponent, too. Topping it off is a system named advantage, which are basically cheeky cheeky cheat points. At the start of each run, you’ll fight a quick tutorial match, after which you’ll pick one of two advantage chips with different rules. One might generate a point of advantage every time you win a round, while another gives you one each time you stand on a score of 17 or higher. Advantage is banked for the length of the match, and you can spend it at any time to exploit certain cards for special effects. Often, these cards are ‘handy’, which means they’ll go into your hand rather than on the table when your draw them. Many others are cards with a base value that either change their effect or enact an additional effect when exploited.

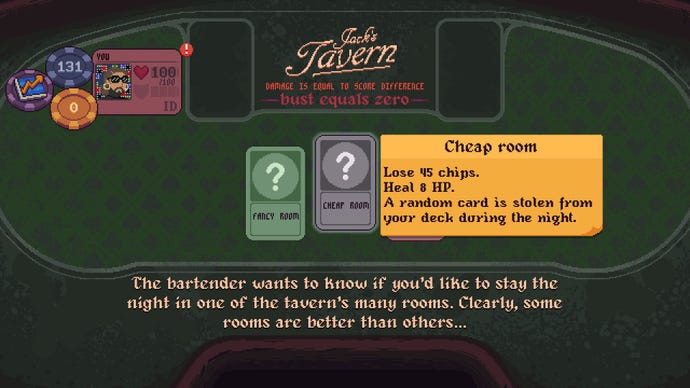

Despite being relegated to a sort of ancillary score system, chips are still incredibly useful. After each opponent, you’ll get a choice of four cards to pick one from. Only three are visible, and you’ll need to pay 21 chips to view and select the fourth. You might spend them to stay a night in a fancy hotel room, healing some health. You might pay a counterfeiter to change the value of your cards, and you’ll sometimes get a chance to just buy more cards outright.

And thems, in very broad terms, are the brakes. What actually makes the game, though, are the breaks: the various keywords and other strange effects you’ll accrue and strategise with, creating felt-scorching combos that can stand up to later opponents. Because you better believe they’ll be breaking things too, and doing it in thematic ways, no less. The necromancer might hit you with multiple Gravecards, which can be exploited to lower their score, throwing off your plans. A later opponent might have a deck specifically built to pile on extra score to your side after you’ve already stood, so you’ll need adequate counters.

This reliance on theming - and what are almost definitely seeded opponents plays rather than true randomness (or at least decks built to make certain plays very common) - is a big part of how the game stays interesting, and frequently quite funny, too. But it's also where my issues start to crop up. Take the second stage boss, for example. He likes to play a '21 of clubs' frequently, which is an instant win, or at least a draw. There’s an easy counterplay here. You just need to find one of a few cards that set his limit to 20, and he’ll keep busting. I’ve beat him without this card, and there are other ways around it, too. But I think this is emblematic of a certain level of railroading, or at least regular deck-checks that I'd usually know much earlier whether I'd be prepared for. It gives you milestones to aim for, keeping things dramatic, but it also meant I'd sometimes start seeing a loss coming very early. Heck, sometimes I’d know after the first few matches.

So you effectively end up with this feeling of limitation and being at the mercy of fate, hanging over each game from the beginning. So I'm winning matches and playing through events, hoping against hope I luck out with the right cards. Because there is a point in the run - not too far either - where playing the fundamentals just won't cut it. You'll need certain cards, or at least that's how it felt. Full disclosure: I am a math idiot, so it’s fully possible there’s some deeply devious failsafes allowing for guaranteed killer decks each run. Either way, I’m rarely landing on them, and what initially felt like freedom didn’t take long shed the Scooby Doo mask and reveal itself to be a kind of disheartening restriction.

And yet, I’m still going to chip away at D&DG. After eight or so hours, my collection tells me I’ve barely seen half the cards, and discovering a new card is more often than not a real joy. I’ve also got many opponents left to face, and starting decks and modifiers to play with. I won’t say D&DG makes losing fun. Playing those opening stages repeatedly quickly lose much appeal past a chance to happen upon a deadly combo early. But it does make losing tolerable, and winning feels great and gets better the more thoroughly you embarrass your opponent. Consider the real promise of the game then, the underlying fantasy. How thoroughly can you make this talking rat regret its life choices? That’s still a fantastic sell.

This review is based on a review build of the game provided by the developer.