UFO 50 review: a pixellated portrait of the 1980s that offers a strange sort of time travel

A retroactive reimagining

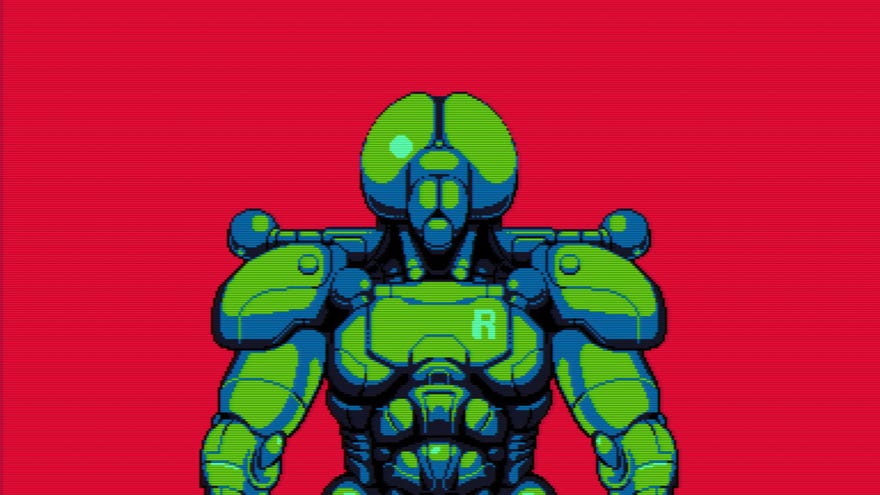

You can't travel back to the 1980s. But what if I told you it was possible to gently warp your memories of that time? UFO 50 is a kart of 50 games that once existed for an old computer system, all lovingly restored by a gang of coders. The old console, of course, is a fiction. The LX-I never existed. But it's a fun pseudo-history against which to create a grab bag of small games (some throwaway, others mighty) all designed with a distinct 80s look. It's an exercise in adhering to an aesthetic. Like an oil painter working with a limited range of colours, the developers of this bundle have stuck to a 32-colour equivalent of the Zorn palette. Yet play a little of each game, and you start to sense the smirk of chronos. These games aren't stuck in the past, but they are enjoying a holiday there.

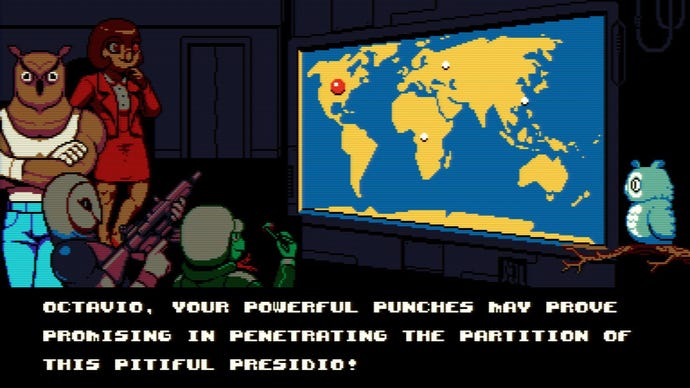

It's also a funny collection, full of jokes and pranks at the player's expense. In one adventure game, tiles may fall on you without warning within seconds of your first movements. In a puzzle game about a chameleon, birds will slurp you up from inside logs just when you thought you understood the rules of camouflage. One medieval strategy game sees your units advance steadily and automatically forward, desperate to charge, unable to even think of defending. This game is called "Attactics"; the title alone a good gag.

There's also comedy (and satisfaction) in discovering exactly what each of these things is. Barbuta, the "oldest" game in the collection, is an unassuming and ancient homebrew Metroidvania that houses glitchy secrets and requires the patience and dedication of a child indoors on a rainy day to make progress. Rail Heist looks like a Sunset Riders-style shooter, but then invites you to play it as an Atari-era Hotline Miami, before you finally realise: "Hang on, is this... an immersive sim!?"

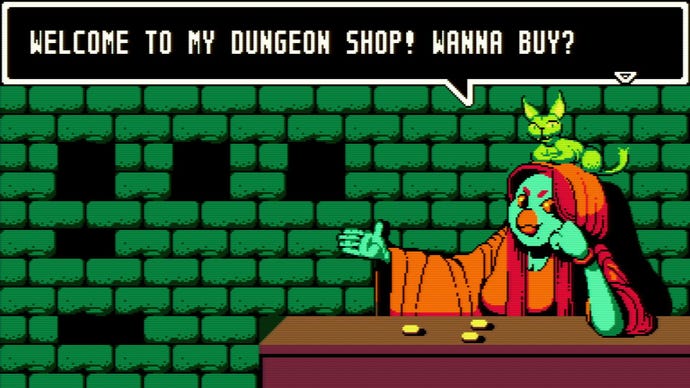

Very few of the games give you any instructions, electing instead to just drop you in. It's a common complaint that modern games hold your hand too much, that they over-tutorialise, and fail to trust the player's perseverance or intelligence. So it's refreshing to get 50 games (albeit of varying depth) which implicitly trust the player to "figure it out". If your patience or brainpower does run out (and mine did a few times) you can simply eject the cartridge and play something else.

To take an example of one of the more compelling oddities, Mooncat is an comically obtuse platformer with some of the most counter-intuitive controls you will encounter this side of 1985. But if you stop and "zoom out" of your preconceived notions of what a controller's inputs ought to do, the idea behind it sort of makes sense. All the direction buttons move you left, and all the face buttons move right. Hey, why not? These are games diegetically invented four decades ago, and it's fun to read Mooncat as the product of a time long before each genre's control schemes developed any sense of orthodoxy.

The whole collection exists in this realm of tension, stretched out like a 40-year-long rubber band. If you squint, you can recognise the games of today between the pixels. Zoldath is a randomly generated explore 'em up set on an alien world where your tools are fuelled by mineral and plant pickups. In other words, it's No Man's Sky but in 1984. Meanwhile, the grid-based laser zappin' of Bug Hunter feels like an NES demake of Into The Breach (and is surprisingly moreish as a result). Velgress is a popcorn platformer that propels you ever higher through fear of decaying platforms. It is like Downwell but going up. That checks out. After all, the designer of Downwell is on the team of (real) developers who made the collection.

"Our goal," say this gang, "is to combine a familiar 8-bit aesthetic with new ideas and modern game design." In this I'd say they succeed. Many of the games are built on design principles or novel gimmicks that simply wouldn't appear in the shooters and platformers of yore, and it's interesting to see where the creators draw a line in terms of what constitutes modern and "classic" game design. (They also inadvertantly make a compilation of games that fit the aesthetics of the "indie darlings" era of the 2010s, but probably because, uh, they are those darlings).

The modern twists are noticeable. Take the concept of "lives" for example. Mortol is a platformer in which you are given a generous 20 lives. But then you are expected to spend those lives turning yourself to stone blocks, or repeatedly launching yourself at the wall to create a step-ladder out of your rigid corpses, thus helping your next "life" get further into the level. Other modern ideas trickle into the games. You can hold down a button to skip long cinematics, for instance. And at least one game ranks you on a three-star scale at the end of every level, adapting the contemporary practice of mobile games.

Against the aesthetics of a pixelated era, such features feel alien, yet weirdly compelling. Imagine watching Humphrey Bogart send a telegram in a 1950s noir, and then text starts appearing on-screen in a WhatsApp speech bubble. Imagine you are enjoying an Akira Kurosawa flick, and suddenly: an unmistakable drone shot. That's what playing UFO 50 is like. It's a compilation of double-takes, a comic provoker of "huh"s, an anachronism bonanza.

It works well mostly because it is so committed to the framing narrative: that this collection exists as a restoration project. There is a meta story (or maybe a "meta-history") to unravel, if you look closely. Each game has its own short developer note. And there's a terminal to enter cheat codes that I suspect will reveal some fun secrets (I didn't crack a single code). Taking it all in at once, the compilation is the story of a hobby's slow professionalisation. Even the menu screens of each game, when taken in chronological order and analysed like individual layers of polar ice, track the changes of their creative pioneers.

Early games are credited in plain text, made by a trio called "Petter, Chun & Smolski". Later games see personal names replaced by a business, "LX Systems", and then "UFO Soft". Eventually the games start sporting a professionally animated logo, complete with a pretty jingle. All personal calling cards are smoothed away. The enigmatic figure of a developer called Thorson Petter appears in early works, creator of games that are often painful or confounding to play, yet strangely sincere in their own user-agnostic way (guess who made Barbuta and Mooncat). Later, his name seems to disappear.

Of course, you don't need to engage in any of this. You can just find the 25 games that include local multiplayer and go ballistic with a pal. There is built-in curation too, letting you filter the games broadly by genre. "Quick play" and "reflex play" cover some arcadey bops, while "thinky games" offers up all the puzzles. And even within these filters there exists a little surprise, a special screen for collectors and obsessives. Perhaps this is the time to say that if you subscribe to Retro Gamer and find yourself watching endless YouTube documentaries about the good old days of pixel platforming, then this will undoubtedly tickle you. It also feels purpose-built for students of game design. Any day now UFO 50 will appear in a video by Mark Brown, and people will wonder why they haven't heard of it (it's because you don't read RPS, you rubes!). Ahem.

If you're not that kind of person - not a retro freak or a game designer yourself - then it's a harder sell. There are games with deceptive depth, engaging enough to grab you by the "one more turn" glands. But you'll have to go in knowing that part of the fun is sifting through the pile to find those. I would flip through three or four games about angry football or samurai tennis with lazy channel-surfing curiosity, only for an hour to vanish like Batman on a nerdy dinosaur-worshipping worker placement game (it's called Avianos, it rules). This is part of the schtick. UFO 50 is not just about playing a bunch of small, tightly made games, it's also about chasing the buzz of discovering something that stands out.

As someone who has spent years curating games to an audience, I'm conflicted about that. It feels a bit like work. I used to trawl through itch.io every week for a free games column on this very site. I understand both the satisfaction and disinterest that comes from panning for gold dust, even in today's overwhelming gamepocalypse. It's definitely gratifying to rummage through UFO 50 and find an Avianos, a Velgress, a Mortol in the pile. But I also didn't get through all 50 of the games in the collection. I barely scratched half. I don't think I could face mining the entire bundle. (Fun side note: this isn't the first time we've been at the coal face with 50 short games, or even 300 in a pirate kart).

Maybe an unfinished pile is to be expected, though. The internet is a capable devourer, and I look forward to reading user reviews about UFO 50 in a way I don't for many other recent releases. Players will be able to evangelize their favourites, list their unmissables, and get into role-playing flame wars about which game in the Campanella Trilogy was best. Perhaps someone out there will explain why you should not give up on the opaque works of Thorson Petter. That would be swell. I don't want to complete Mooncat, that baffling platformer, but I do want to watch the 20-minute retrospective from the bearded 50-year-old who has.