Final Fantasy 16 review: if it were half as big it'd be twice as good

Clive service game

I'm reasonably sure Final Fantasy 16 isn't the longest Final Fantasy I've ever played, but it feels that way, for a multitude of reasons. The major one is that a lot of its quests exist to create distance between places and plot beats. They are overwritten errands such as bringing people lunch or fetching herbs or carrying letters - dessicated, MMO-ish fare, thrust into a moderately enjoyable action-RPG for the sake of incremental worldbuilding and scale.

Even the more exciting varieties follow a formula you soon internalise: a colourful but basically unnecessary chinwag; a hike through a scenic but not very intriguing stretch of map you've probably already seen in part; a fight with a few monsters you've almost certainly beaten up a dozen times before. There are some decent sidequests towards the end - tangents dedicated to core companions, before you mount your final run on the Big Bad. The majority of quests are also optional, if you don't mind skipping the level-up rewards. But you have no way of knowing which are worth skipping, and to be wholly unromantic, you have no way of skipping out on an appropriate percentage of the asking price. Perhaps most damningly of all, there is no minigame - no life-devouring cardgame, snowboard section or weirdo excursion into animal husbandry - to console you when all the busyworking gets too much.

Another reason Final Fantasy 16 feels longer than most is that you'll spend essentially all of it in the shoes of one character, Ben Starr's disgraced and outcast noble Clive Rosfeld. Clive isn't terrible company, in fairness. He's a glowering bundle of guilt and grief who slowly thaws and learns to live again, as is generally the fate of glowering bundles of guilt and grief in video game stories. I found him deeply unlovely at first, but was surprised by how much I'd warmed to him 50 hours later, and that isn't just Stockholm Syndrome: Clive matures believably, making or re-establishing connections, scraping together a purpose and even achieving a vocal setting beyond "anguished growl". All the same, I would not have chosen to spend 50 hours watching him learn not to be such a massive grumpyface, and I can't say the rest of the cast made a lasting impression on me either.

FF16 does have some very charismatic characters. In the early game, there's Ralph Inneson's Cid, a distressingly sexy Loiner, all twinkle and rumble and wedge of bare chest, who serves as Clive's mentor. Later on, there's Stewart Clarke's Dion, Final Fantasy's (somehow) first openly gay character and a melancholy perfect prince who is engulfed in toxic family dynamics of his own. Looking back, however, I feel like even Cid and Dion are all surface shimmer - I remember them chiefly as collections of clothing, poses and accents that are fundamentally props for Clive's ponderous journey of self-discovery. And for every solid supporting act FF16 has, it treats you to a bunch of paper tigers. The women of the cast are especially poorly served - they're a pretty bald set of sexist caricatures in a story that takes too much inspiration from Game Of Thrones. Clive's childhood sweetheart Jill, played by Susannah Fielding, is a perpetually wilting wallflower. Nina Yndis's Benedikta, henchwoman of a sinister, remote kingdom, is a prancing seductress. Clive's mother Anabella, performed by Christina Cole, is a viperish hag.

The focus on Clive isn't purely born of a wish to tell a more straightforward hero story than the party-based shenanigans of old. Perhaps Final Fantasy 16's cleverest flourish is that it's a steady deconstruction of Clive's centrality. Before we get into that, I guess I should talk setting. FF16 unfolds in Valisthea, a high fantasy world of kingdoms who are fighting tooth and nail for control of various supernatural entities or resources. There are the Mothercrystals, glittering mana mountains whose fragments are the source of most of Valisthea's magic. There are the Bearers, a despised subclass of enslaved humans who can wield magic without using crystals. And there are the Eikons, godlike creatures based on Final Fantasy's summons, together with the much-coveted human Dominants who can channel their powers.

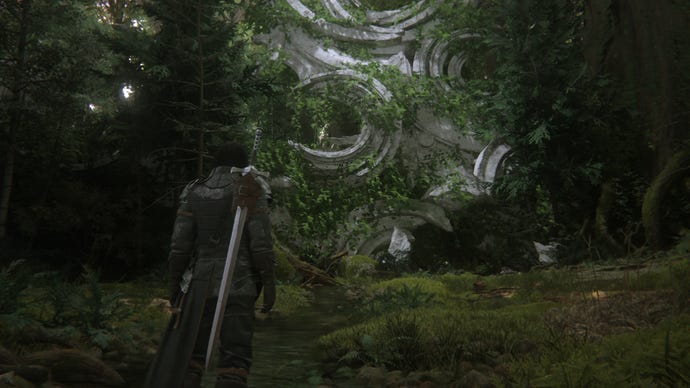

As a piece of worldbuilding, Valisthea is alright. It's got some very shiny castles, some plausibly disorderly bazaars, and a few nicely enveloping underground crypts, created by the obligatory super-advanced elder race. Its limitation is partly homogeneity, in a couple of senses. On the one hand, it's a bunch of branching corridors and arenas that can feel, if not look, interchangeable. On the other, the population are conspicuously white with a predominantly Anglophone British voice cast, but many areas take heavy inspiration from north Africa and the Middle East, which makes Valisthea resemble some kind of expat colony or worse, piece of appropriative cosplay. The medieval fantasy aesthetic occasionally comes off as dry, next to the richer ambient colour palettes and geography of the older turn-based games, and certain social structures simply aren't that convincing: the Bearers stuff is a ramshackle take on slavery that feels like it's based chiefly on representations of such things in other video games.

Aside from the constant warring over MacGuffins, the realm is threatened by a mysterious case of habitat death, the Blight, which appears linked to the realm's magic. Clive's motivation at the start of the game is finding those who engineered his family's downfall, including a strange rogue Dominant who can channel the demonic Ifrit. But he's eventually drawn into the role of world-saver, setting out from a base in the middle of the world map to knock over various antagonists while plumbing the origins of the Blight. The latter third of the game moves beyond the feuding over land and resources to a metaphysical confrontation with puppetmasters in the shadows.

Clive's defining capacity as both a playable character and a work of narrative is that he can absorb the powers of the Dominants he befriends or defeats; once toppled or persuaded, they endow him with suites of unlockable attacks, evasive moves and super abilities. It might feel like a slap in the face for Final Fantasy's traditional party-based format: all of FF16's grandest supporting characters ultimately exist as upgrade fuel for sulky himbo Clive, so that he can conjure up darkswords and do aerial juggles. Small wonder they feel so superficial. And this is sort of the point.

Clive's ability to dominate the Dominants and concentrate Valisthea's overall agency within himself isn't just the usual boss-upgrade treadmill, but a subplot with a sinister dimension. Learning what this entails is a lot of fun. But it also requires a gigantic preamble, and even as a Squaresoft4ever diehard who is well accustomed to Final Foreshadowing, I don't think it's quite worth the legwork.

Nor, I would argue is the combat, even though the combat is good. FF16 is sort of Devil May Cry with a million times the cutscenes. Fights take place in the same world as exploration, and see you performing combos and special moves with a cooldown to both damage and, eventually, stagger an enemy, which (as in FF13) opens a window in which your attacks hit harder and they don't fight back.

The unlockable Eikon suites slowly layer up this foundation. You can equip and switch between three at once in real-time, and they fit certain playstyles: Garuda is about speed and juggles, for example, while Bahumut's signature trick is a charging AOE lightning bombardment that requires you to avoid damage. There's a fair amount of theorycrafting to be done once you've hooked up with enough Eikons. The controls are intuitive, and the animations and effects are as fancy as you'd expect from a numbered FF (albeit with spotty performance), but again, it's all smeared too thin. You will fight a lot of foes who exist to create friction, and when quests are dragging on, it's tempting to brute-force the stagger mechanic rather than playing with the options at your disposal.

If the bread-and-butter skirmishes get boring, the crowning bossfights are some reprieve. Most begin as larger-than-life regular battles, with participants fully incarnating as Eikons with distinct movesets. From there, they escalate into absolutely shameless, full-bore QTE-driven cinematics that stand proudly alongside the wilder summons of the turn-based games. The best weave in mechanics from other genres, like bullet hell and on-rails shooting. You could argue that these crescendoes are all the more awe-inspiring for existing in a game's worth of quests to deliver lunch, but I think that's letting Square Enix off easy. In a shorter, more focused RPG that is less tentative about its strengths, less fixated on scale, these bosses would have really sung.

Still, I'm not sure even cutting the playlength dramatically would have made FF16's fundamentals essential. The use of a single protagonist and the specific choice of Clive as frontman are a glass ceiling the game strains to move beyond, though it does, at least, use that glass ceiling as a mirror.

It's a lavishly made and occasionally engrossing epic, definitely a game you'll relish more if, unlike the average reviewer, you can afford to take your time. But it doesn't have the wackiness and starpower of its most obvious rivals, the Final Fantasy 7 remakes. Its major characters would be bit-parts in Midgar, filling out the crowd at Seventh Heaven. Jill is the lady by the jukebox trying not to get mistaken for a mop. Cid makes for a captivating presence behind the bar, but he's clocking off early tonight. And Clive? Clive is that woebegone regular who's sort of a hit with the ladies but who insists on telling everybody about his domestic quarrels and who just won't sodding leave.